REVIEW: Jina. Part 2. Gateway & Executor

a Python framework for building AI services and pipelines

This is the second and concluding part of our deep-dive code-review of Jina, a Python framework for building multimodal AI services and pipelines. In the first part of the review we talked about the problem the product solves and highlighted its main features. Then we took a closer look at its reference implementations of Python clients, including gRPC and JSON over HTTP ones. Throughout our assessment, we pinpointed several opportunities for enhancement, from the readability and maintainability of the codebase to substantial performance bottlenecks.

REVIEW: Jina. Part 1. Clients

https://github.com/jina-ai/jina: v3.19.1 dated July 19th 2023 When it comes to machine learning model serving, there are plenty of open-source solutions that address this problem to different extents and from various angles. Some of those solutions put stronger emphases on developer experience and interoperability. Others focus more on infrastructure, ob…

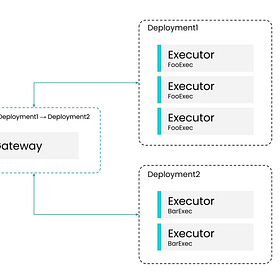

Let’s take another look at the high-level Jina’s architecture:

We now know that Jina supports multiple protocols and is bundled with reference Client implementations for them. We also understand that the framework offers building blocks such as Deployments and Flows that facilitate advanced orchestration. Both Gateway and Executor components can serve the mentioned protocols, but Gateways, being part of Flows, are also responsible for coordinating and routing traffic between Executors. Unlike the Client ←→ Gateway communication, Gateway and Executors are connected exclusively by an internal gRPC-based protocol. This is a good choice as it simplifies maintenance and reduces complexity.

In this post we will explore how the Gateway and Executor components are implemented.

Orchestration

One interesting feature of Jina is its support of containerized deployments. The framework can generate Docker Compose and Kubernetes manifests based on the definitions of Flows and Deployments. This is quite handy and definitely saves some time.

But Jina also tries to implement its own orchestration logic based on Docker and local processes, where it spawns Docker containers, introduces a notion of a Pod and more. We intentionally did not explore this part of the system since it is not the only option and developers can simply choose an alternative production-grade deployment solution like Kubernetes.

Gateway

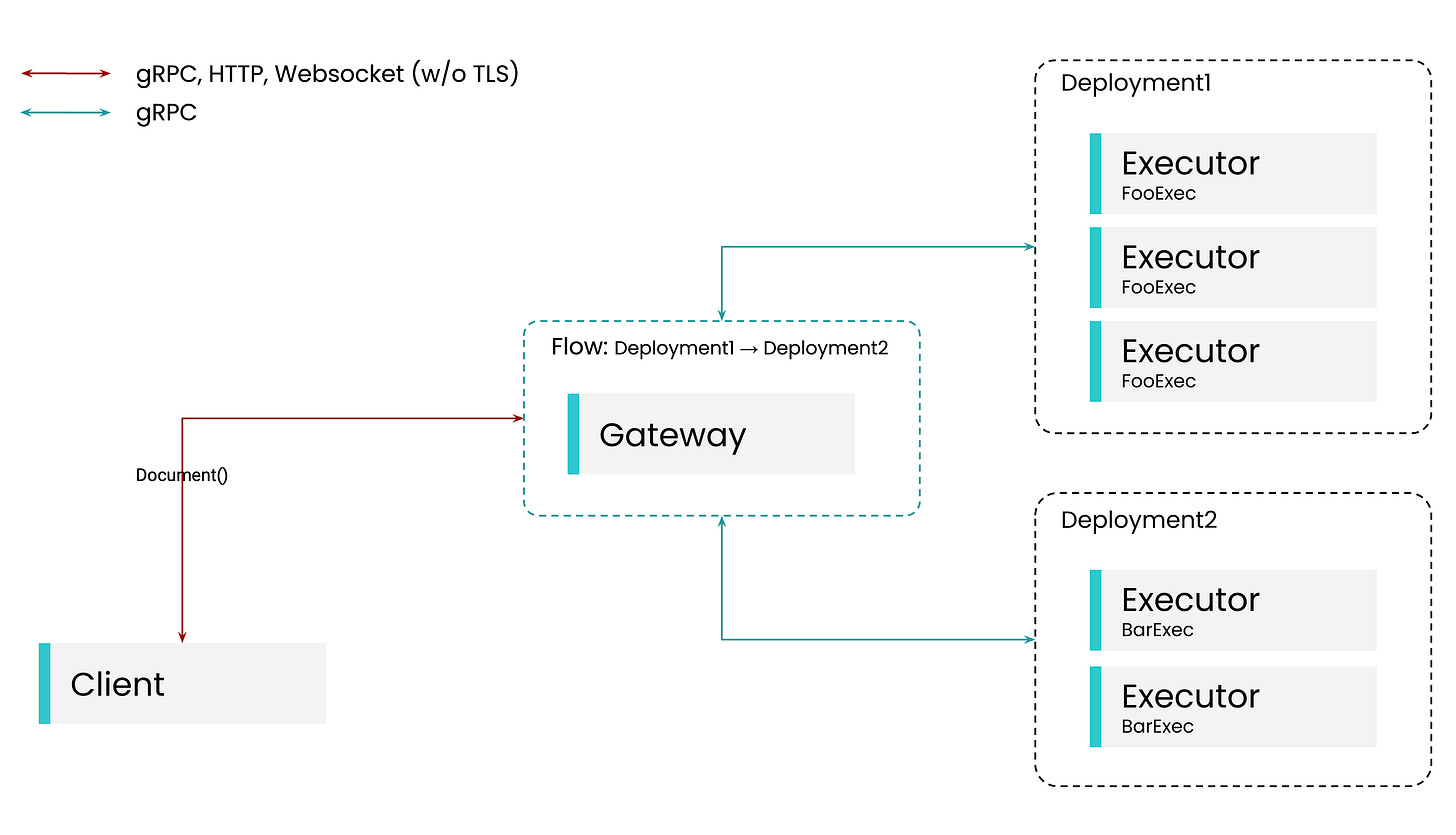

Jina is bundled with a simple CLI tool that allows launching its components, such as Gateways or Executors. Here’s how the entrypoint for launching a Gateway looks like:

jina_cli/api.py#L85

As we can see, on the highest level a Gateway is comprised of an instance of the AsyncNewLoopRuntime class with an instance of the GatewayRequestHandler class as an argument. A similar combination is applied to Executors, although in that case there’s another level of indirection. The run_forever method above simply blocks the execution while it is serving one or more protocols mentioned earlier.

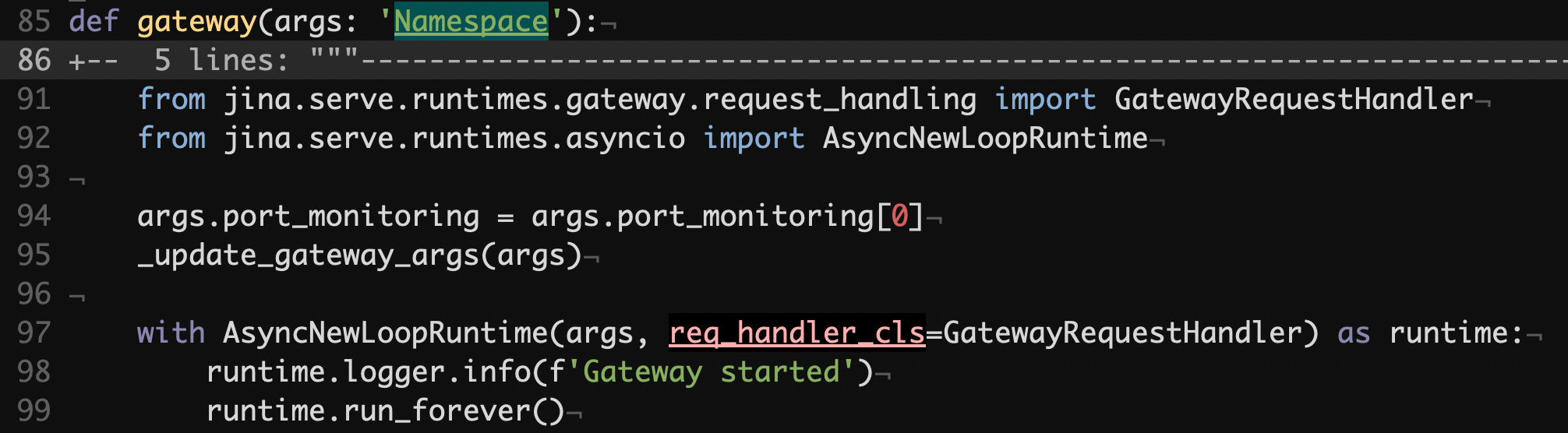

If we strip through the noice of AsyncNewLoopRuntime, we will find that the implementation creates a server using the _get_server method and then runs it.

jina/serve/runtimes/asyncio.py#L33

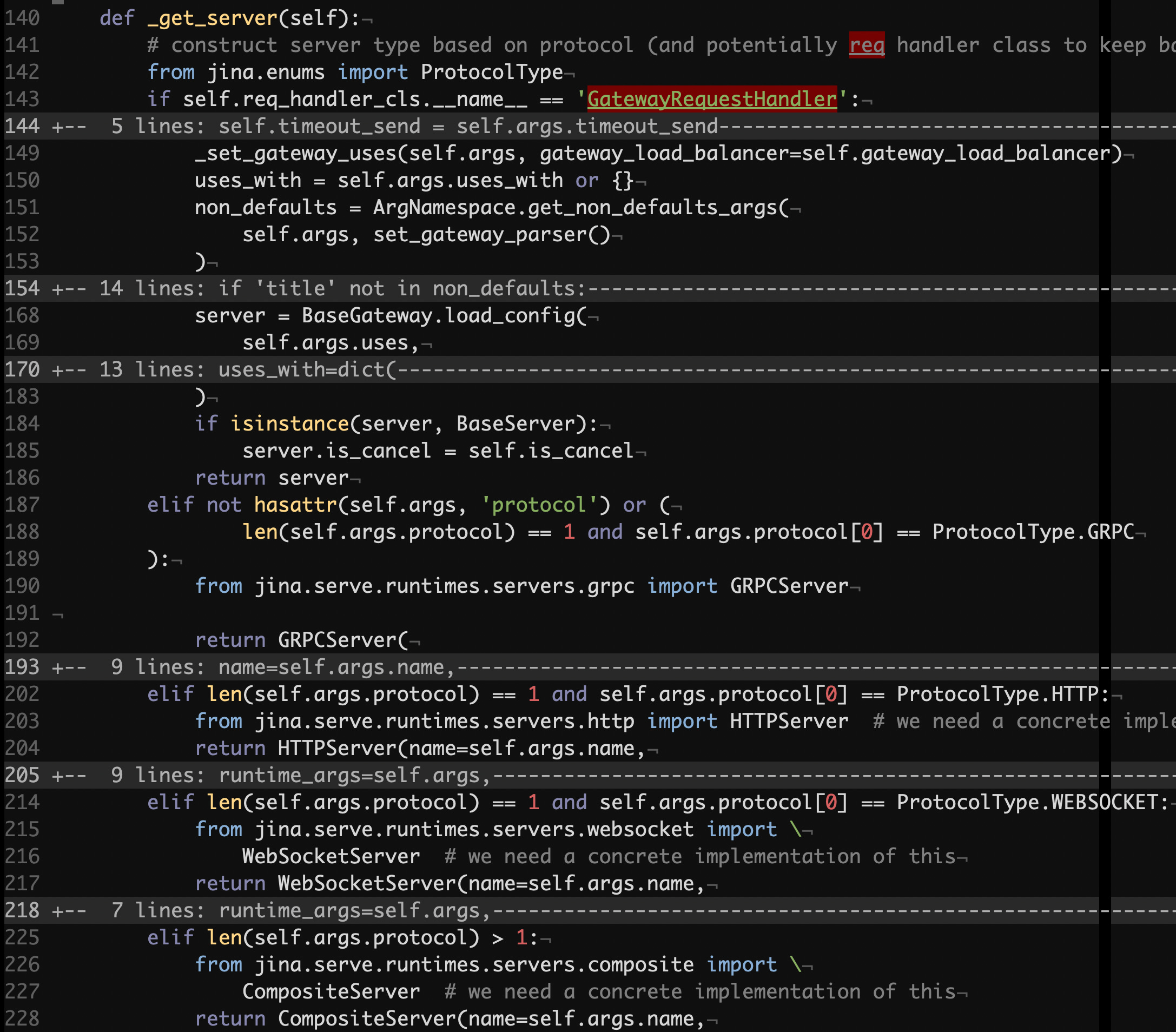

_get_server is a long factory that picks a BaseServer implementation based on the configuration that sits in self.args.

jina/serve/runtimes/asyncio.py#L140

Unfortunately, the quality of the code above is not exemplary. Let’s dive into details.

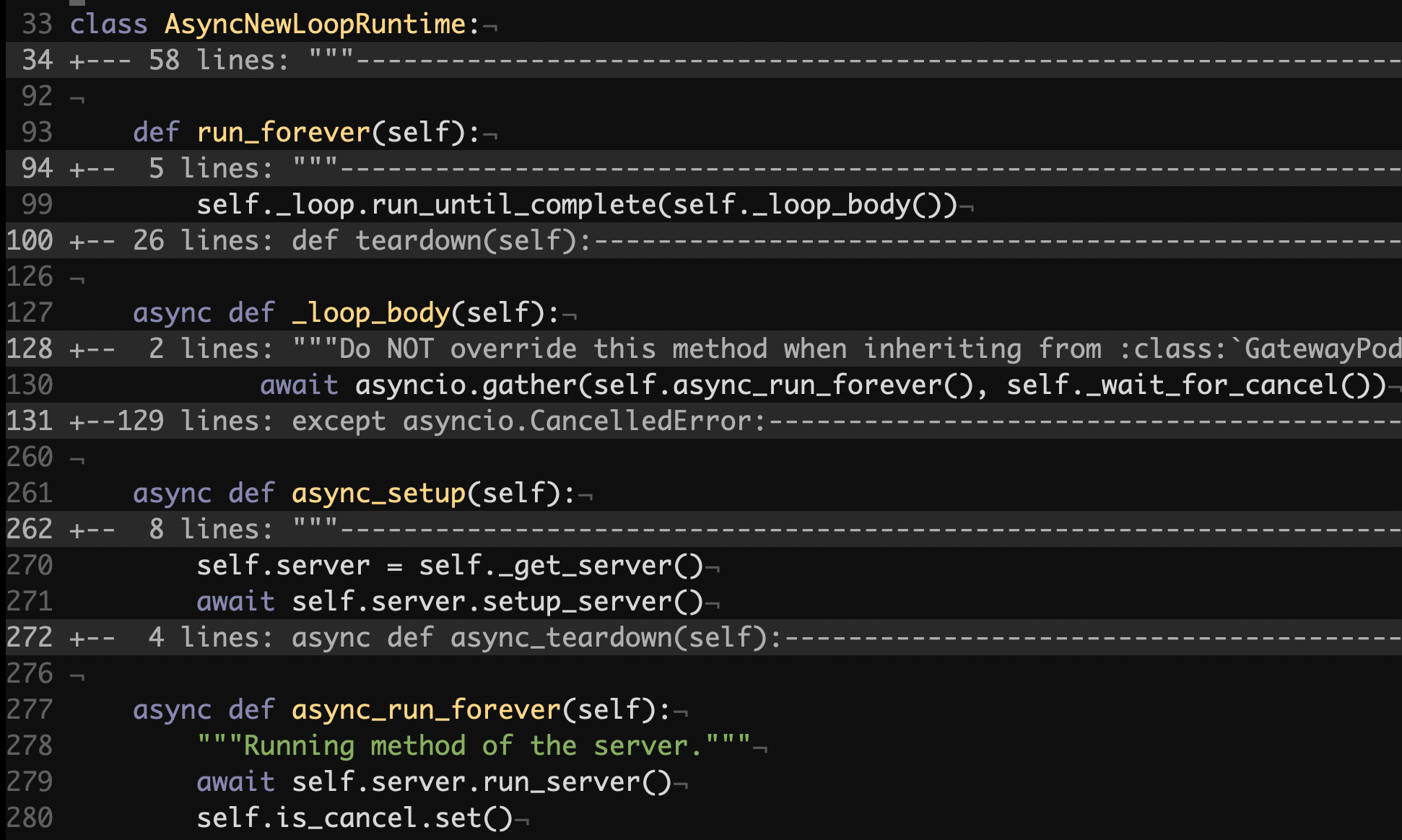

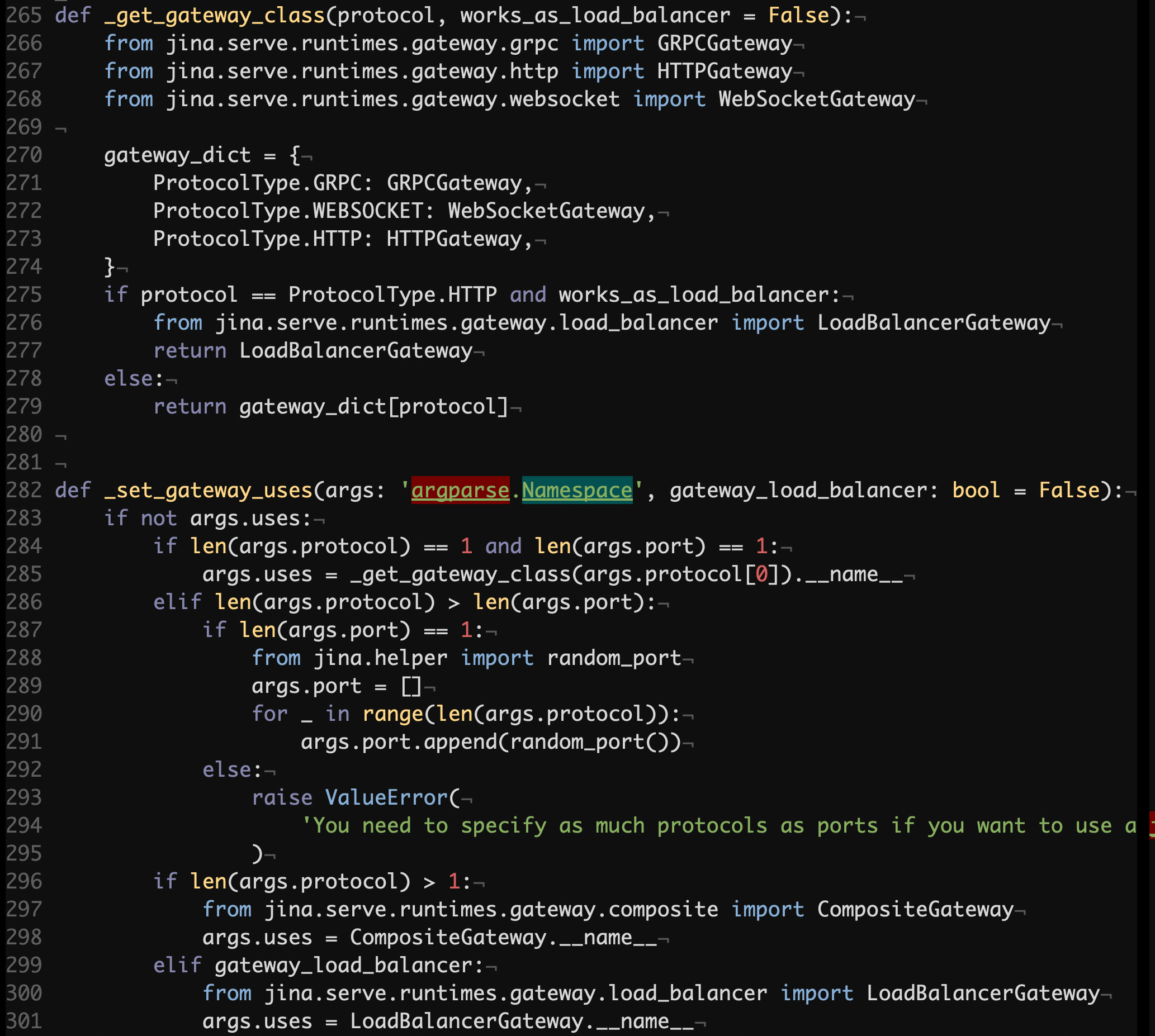

So, what is self.args? According to the type annotation it is argparse.Namespace. Does it belong there? Of course not. Typically it belongs to code that parses arguments to the program and then instantiates dedicated data structures that hold configuration information. Those classes are usually strictly typed, and allow having additional behavior. For example, one could have a dataclass named Config that would have a boolean property is_protocol_grpc etc.

Instead we see all that clumsy repetitive conditional logic spanning all available horizontal screen space.

The issue with argparse.Namespace is systematic:

$ rg -c Namespace **/*.py | awk -F ":" '{sum+=$2} END {print sum}'

170

$ rg -c SimpleNamespace **/*.py | awk -F ":" '{sum+=$2} END {print sum}'

30

$ rg -c ArgNamespace **/*.py | awk -F ":" '{sum+=$2} END {print sum}'

38

$ rg -c argparse.Namespace **/*.py | awk -F ":" '{sum+=$2} END {print sum}'

25It’s everywhere: in the orchestration logic, in the gateway and executor runtimes etc. This might seem like a minor issue, but it has significant implications in terms of maintainability of the codebase.

The Jina team even implemented ArgNamespace that helps with using argparse.Namespace. And on top of this the codebase also leverages types.SimpleNamespace for similar reasons. In essence this is like explicitly abusing dict as a primary data structure.

The line that checks whether the name of the request handler class is “GatewayRequestHandler” is indicative of the lack of well-thought object design. You will see this again and again throughout the codebase. The great news is, therefore, that there is plenty of room for improvement and lots of opportunities to do a better job, right?

Another unexpected finding is that self.args gets mutated along the way. Instead of keeping all the configuration logic organized in a centralized and controlled way, we see bits and pieces of it spread throughout the modules. This is on par with code that sets values to its process’ environment variables found in some unexpected places in the codebase.

jina/parsers/helper.py#L265

Certainly, AsyncNewLoopRuntime isn’t the place to trigger the logic above. But it so happens that the _set_gateway_uses function is a factory that produces an instance of Gateway. Specifically, a concrete implementation of Gateway.

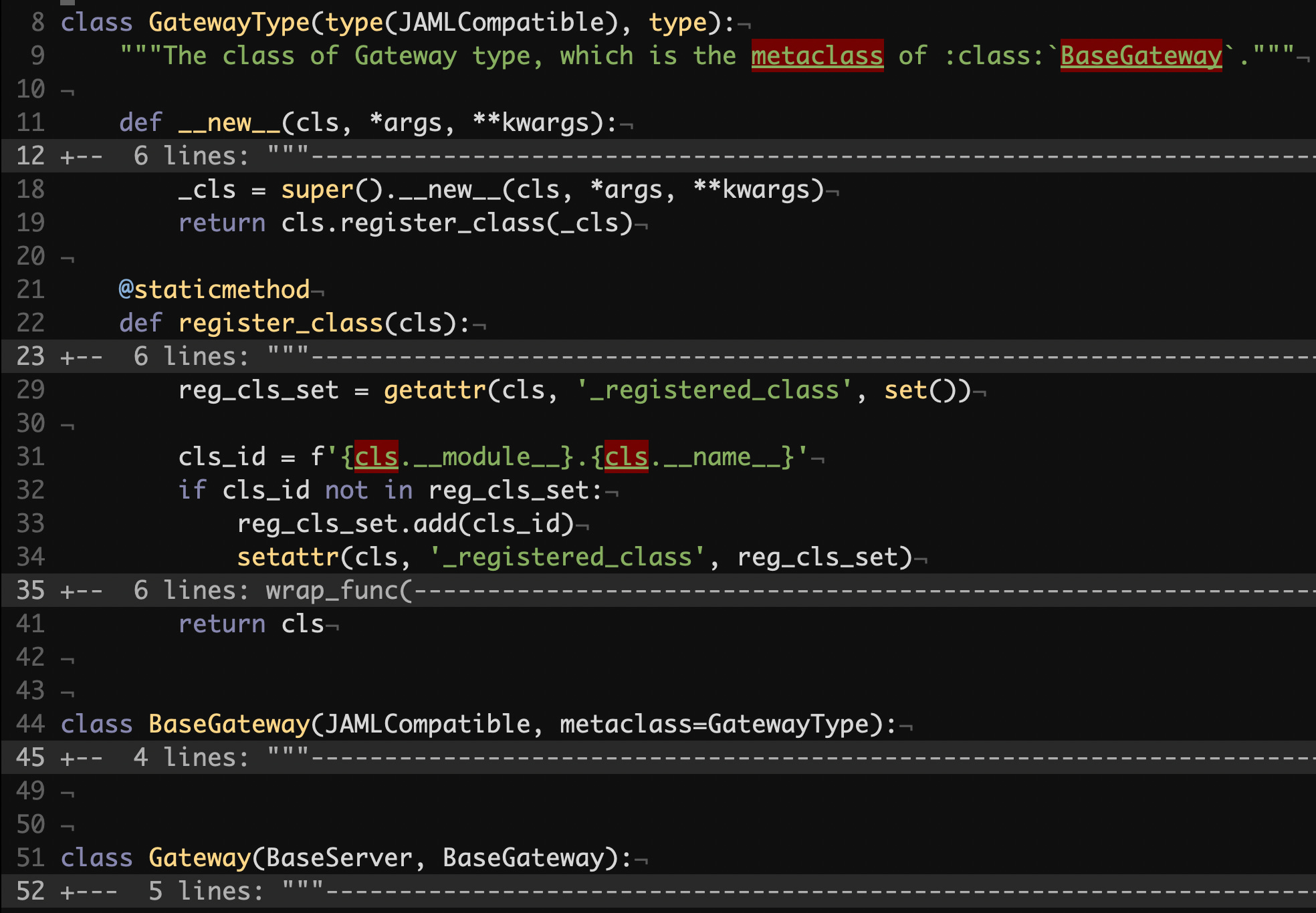

Like with Clients, Jina’s backend code is full of the mixin pattern. And similarly so it is abused instead of relying on composition more often. As you can see below, both BaseGateway and Gateway classes do not have bodies. For BaseGateway it may be justified as it combines a base class capable of registering subclasses, which may be useful in some cases. But not so for Gateway and its children.

What’s more is that BaseGateway is JAMLCompatible. We will not be diving into this notion too deep, but it is worth mentioning that JAMLCompatible bundles functionality for parsing YAML in a certain way.

Wait a second. A Gateway is not only a BaseServer, it also somehow gets configured by YAML in run time. And this goes on top of the configuration challenges we brought up earlier. Isn’t it too much for Gateway? Apparently no.

jina/serve/runtimes/gateway/gateway.py#L8

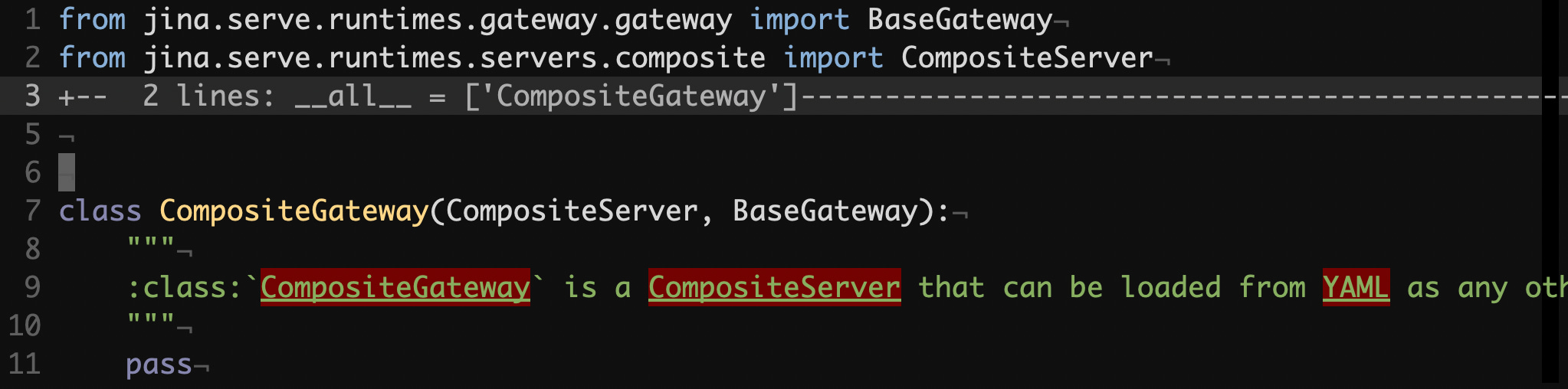

If Gateway inherits from both BaseServer and BaseGateway, there must be some relation between the two. Perhaps JAMLCompatible represents this relationship. Or not. It is assumed by the authors, but it isn’t really clear from the code. If we look at the “implementation” of CompositeGateway below, we see that it is similarly a class with no body that inherits from CompositeServer and BaseGateway. Wouldn’t a single Gateway parametrized by a generic BaseServer suffice. Or simply a properly configured Server implementation?

jina/serve/runtimes/gateway/composite/__init__.py#L1

CompositeGateway is based on CompositeServer which simply runs a collection of servers corresponding to the specified set of protocols. Pretty straightforward. An implementation of BaseServer for a specific protocol might be interesting. Here’s how GRPCServer gets initialized: